What I remember best are the leeches. African and Latin American rainforests don’t have them. Southeast Asian forests are literally crawling with leeches—when you stop walking, the forest floor seems to undulate as they march like inchworms towards you! When I first visited Malaysia’s rainforests, to evaluate the Wildlife Conservation Society’s program there a decade ago, the team issued me—the newbie—with their one pair of tightly woven canvas “leech socks.” They seemed to work—until I saw blood gushing from my watch. Two leeches had leaped off trees and hidden under there, injecting their anesthetic and anticoagulant and feasting away!

Southeast Asian rainforests have leeches because they are the wettest and oldest of the world’s three great rainforests. As a result, they are by many measures the most biodiverse. They are also, after decades of industrial development, the most threatened.

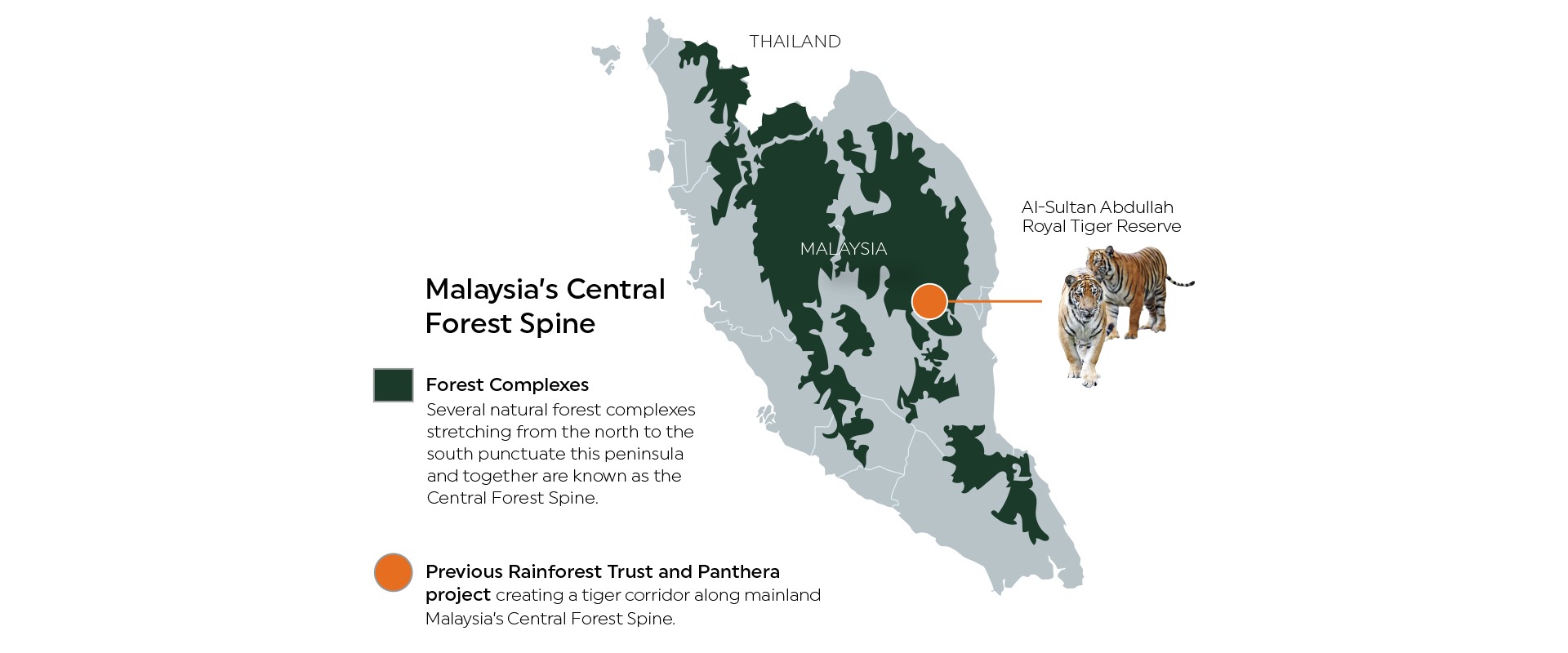

Our evaluation team first visited the “central spine” of mainland Malaysia where the conservation community dreamed of linking three great national parks into a continuous forest belt for tigers and other endangered species. The obstacle was the rapid conversion of the forest between the parks into palm oil plantations and, especially, rubber tree plantations, often driven by land-grabbers and corrupt officials.

From mainland Malaysia we proceeded to the state of Sarawak on the island of Borneo where the impact of oil palm plantations has been even more dire. Visiting the intact forests of Sarawak required driving through seemingly endless commercial plantations—row upon row of palms in military precision, devoid of wildlife and biodiversity. Most of these were planted in the last few decades on land deforested for the purpose. Tragically, the worst impacted forests were the most important ones for both biodiversity and climate. These were the lowland forests, accessible to roads and ports, hot and wet and full of species, and in many cases sitting on vast deposits of accumulated organic matter, peat, which decays and burns when the forest is cut, belching vast quantities of carbon dioxide (and smoke and other pollutants) into the atmosphere.

Gunung Api-Mulu National Park-Sarawak, Borneo, by Chien Lee

For me, one of the great pleasures of coming to Rainforest Trust four years ago was the opportunity to work more intensively tosave the remaining rainforests of Latin America and Asia-Pacific, rather than focusing mainly on Africa as I had at WCS. So I was super excited when, two years ago, the international NGO Panthera came to Rainforest Trust to implement exactly the conservation vision articulated to me in mainland Malaysia 10 years ago—creating a tiger corridor along mainland Malaysia’s central spine. Panthera proposed to protect land to the south of the largest of the region’s three parks, Taman Negara (literally “national park” in Malaysian), building on progress made in a previous Rainforest Trust project with a local organization, Rimba. And, indeed, the Al-Sultan Abdullah Royal Tiger Reserve was officially designated in August 2023. Rainforest Trust has also, through the years, helped to slow the rate of oil palm expansion and protect the critical remaining forests on the island of Borneo—to date, our supporters have helped to save 962,371 acres there, an area the size of Rhode Island, and our current projects are seeking to protect 400,000 more.

Rainforest Trust’s board just approved our latest Borneo project, partnering with a local NGO and an Indigenous community to protect a vast (for Southeast Asia) tract of 54,000 acres of intact rainforest in the Indonesian area of Borneo, the province of Kalimantan, near the border with Sarawak. This tract, together with an adjacent area whose protection we launched a year ago, will form a vast conservation landscape and enable orangutans to roam from the protected areas of Sarawak peat forests of West Kalimantan. This particular land is also remarkable for harboring eight species of hornbills, the large, spectacular, intelligent, and pair-bonded birds that are so critical to seed dispersal and forest regeneration in Southeast Asia.

Male and female Wreathed Hornbills, by Independent Birds

Borneo is the third largest island in the world. To the east lies the second largest, New Guinea, which I have yet to visit. But Rainforest Trust has been focused on New Guinea for many years, for several reasons. It remains 65% forested, and almost all of that is intact, high-integrity forest—making it by far the largest remaining block of high-integrity tropical forest in the Asia-Pacific region. New Guinea is also the most floristically diverse island on Earth. Similar to Madagascar, the island harbors scores of species found only here. And what species! Birds-of-paradise and bowerbirds, 49 species of marsupials (second only to Australia), including 12 of the world’s 14 tree kangaroos, and, weirdest of all, monotremes (egg-laying mammals). The steep ridges and valleys of the island seem to have encouraged the subdivision of populations and spawning of new species. Remarkably, cultural and biological evolution seem to have followed similar trajectories, with human clans isolated on neighboring ridges. As a result, New Guinea has by far the highest diversity of languages per area on Earth, mirroring the biological diversity.

The steep topography and division of land between fiercely competitive clans who own it have also slowed resource extraction and foreign influence—hence the remarkable intactness of New Guinea’s forests and biodiversity. But that is rapidly changing as the oil palm, logging, and mining, and oil and gas investors of Malaysia and Indonesia look east. Like Borneo, the island is politically divided, with Indonesian Papua to the west and the independent nation Papua New Guinea (PNG) to the east. Neither is easy to work in, Indonesia because of the complex federal system and bureaucracy, and PNG because of low capacity in both the government and non- profit sector. The subdivision of land between clans, which has been so positive for conservation in the past, also poses challenges for negotiating land-use protection at scale in order to ward off threats in the present and future.

Rainforest Trust has had extraordinary success on both sides of New Guinea in spite of the challenges. Our donors have helped protect 4,324 acres so far in Indonesian Papua, with 200,000 more in progress. In PNG, our supporters have sponsored one highly successful previous project, to create a large (for PNG) community-based protected area of 233,187 acres with the Tree Kangaroo Research Project in the Huon Peninsula in the east of the country. But we have found it challenging to find projects to replicate these successes. So on both sides of the border we took action. In Indonesian Papua, with the support of our Conservation Action Fund donors, we sponsored the region’s most dynamic conservation leader, Bustar Maitar, and his NGO EcoNusa to work with the government, local communities, conservationists, and other NGOs to create a blueprint for conservation and land-use planning in the Crown Jewel of Papua to protect 13 distinct rainforest ecosystems in a region where 93% of the forest remains intact. And in PNG, one of our most generous and far-sighted donors sponsored us to partner with the new National Biodiversity Foundation to identify and support the development of the most promising conservation leaders, NGOs, and projects.

Torricelli Mountain Range

Western Crowned Pigeon, by Ondrej Prosicky

Both these investments have now borne fruit, and our board just approved two full projects in New Guinea. The first, in Indonesian Papua, will work with EcoNusa and Indigenous communities to protect four critical areas of the Crown Jewel of Papua as community forests, ensuring a future for unique and threatened species including the Western Long-beaked Echidna (CR), Black-spotted Cuscus (CR), Spectacled Flying Fox (EN), Western Crowned Pigeon (VU) and Pesquet’s Parrot (VU). The second, in PNG, will support a local partner organization led by an Australian couple who have committed their lives to the biodiversity of PNG, targeting for protection one of the richest, most biodiverse, unprotected regions of the island—the completely unprotected Torricelli Mountain Range. The community conservation area the project will create harbors, astonishingly, four species of Critically Endangered marsupials, including 30% of the range of the Golden-mantled Tree Kangaroo, 40% of the range of the Tenkile Tree Kangaroo, and 75% of the range of the Northern Glider. I’ve taken the liberty to attach prospectuses for the three extraordinary projects in Borneo, Indonesian Papua, and Papua New Guinea that were just approved by our board and which I discuss above. Southeast Asia does not always attract the level of conservation attention of the Amazon or the Congo—which is a shame, because its creatures are, if anything, even more diverse and threatened. I have no doubt it will be challenging for us to raise the full funds for these projects. Will you consider joining me in working to save these spectacular species and ecosystems? Perhaps you might even be willing to offer a matching gift for donors visiting our website? I hope, in due course, we can take some key supporters to visit these wet and wild forests—and maybe even experience an attack of forest leeches! Meanwhile, thank you so much for your time and your tremendous commitment to the future of our planet and all its inhabitants.

With all best wishes and sincere thanks.

James C. Deutsch

CEO, Rainforest Trust

Healthy Rainforests. Healthy Planet.

Healthy rainforests are critical to a healthy planet. Creating protected areas is the most effective way to protect endangered animals, safeguard biodiversity, stop deforestation, and maintain the health of all species on our planet.

Sign up to receive the latest updates

"*" indicates required fields

100% of your money goes to save habitat and protect threatened species.

Our Board members and other supporters cover our operating costs, so you can give knowing your whole gift will protect rainforests.